The

Barnes Family Story

Contents

Records from Kent

Family History Society

The Family of

William and Harriet Barnes

The Family of

William Robert and Sarah Barnes.

The first

generation born in New Zealand - John Barnes

The Family of John

and Hannah Barnes (nee Old)

The Family of

Thomas and Francis Cole (nee Barnes)

The Next Generation

- the descendents of John and Hannah Barnes

The Family of

Albert and Francis Campbell (nee Barnes)

The family of

George and Ethel Barnes (nee Cowie)

The Family of

Arthur and Olive Barnes (nee Wellard)

The Family of

Victor and Constance Barnes

Family History and

Early Recollections A.C. Barnes, 1965

Introduction

The Barnes Family Story deals with the story of my father, Arthur Cyril Barnes (born 13th November 1901), his ancestors, and his brothers and sisters and their families.

My father and mother wrote most of the notes, and the perspective is theirs unless indicated otherwise. Their original documents: -

· Barnes Genealogy. The ancestry of the Barnes family. General Genealogical information.

· Family History and Early Recollections, A.C. Barnes, 1965. A personal family history written by my father.

· Early Recollections. My father's recollections of the world that he grew up in.

These

documents have been scanned, formatted, and linked to this document, but are

otherwise unchanged. I have updated the Family History, combined it with

the Geneology, and illustrated it with maps and photos.

In 2012 I added charts, converted it to HTML, linked names to records in the GDB, and put it on to FamNet. NB: readers may need to be logged into FamNet to follow the links.

The Barnes Family in England

(These notes were prepared by my parents, probably about 1970 (latest entry is 1974))

Cranbrook

Cranbrook is a little market town and parish, pleasantly situated in the Weald of Kent. It has a large trade in hops and malt. From the fourteenth century to the seventeenth it was a busy seat of the broadcloth manufacture introduced there by the Flemings. St Dunstan’s church contains a celebrated baptistery. Population of parish 3829 in 1931 (Everyman’s Encyclopaedia). Cranbrook is situated 13 miles south of Maidstone.

The Barnes Family in England

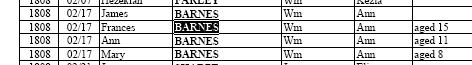

Records from Kent Family History Society

This section added by Robert Barnes in 2006, updated 2012.

From a CD of parish registers from the Kent Family History Society, records in the Cranbrook Christening register suggest the following ancestry for William Barnes. This is all extremely tentative, as the records give only abbreviated names (eg “Wm” which is presumably “William”), and so one can’t link to anybody in other parishes, nor be sure that the ancestry is correct. With this qualification:-

From the baptism records of the Cranbrook parish, 1559-1812: -

P 306 is this record: -

![]()

which is presumably the William who, with his family, emigrated to New Zealand in 1841. The spelling, Barns, explains why Mum originally had this spelling in her notes.

Going back about twenty years, this could be his father: -

![]()

and his father’s siblings: -

![]()

The full list of Barnes entries from this register: -

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Added 2012,

RB: -

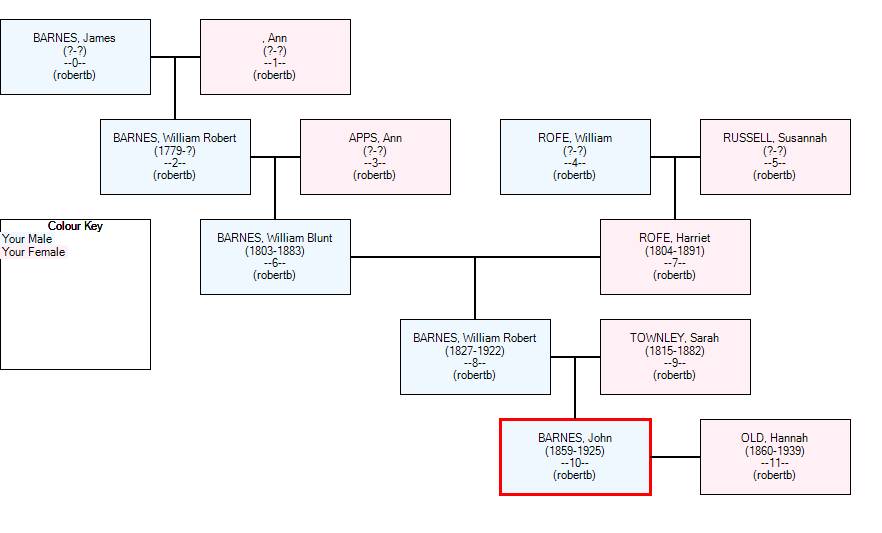

While on a

trip to SLC in 2011 I was able to spend a little time in the Family History

Library. From their microfiche I was

able to confirm this ancestry, and the next generation too. The ancestry is given in the GDB: here is an

ancestral chart from my grandfather: -

William Barnes/Ann Apps

Back to my Parent’s original narrative: -

It was in the parish of Cranbrook that on Oct. 23, 1800 William Barnes married Ann Apps (we had always understood that this William married Ann Blunt - hence his second name).

The baptismal dates of their children are as follows:-

1801, Dec 25th Robert. Born Dec 25th, died 1834, aged 33 Yrs.

1803, May I

William Born

March 20, 1803. died March 3, 1883 at Wellington, N. Z. and was buried in the

Karori Anglican Cemetery.

This William with his wife and family arrived in Wellington, N.Z. November 3,

1841 and was the first of the family in New Zealand.

1805, Mar 24 Mary Ann

1806, Aug. 31 Martha

1808, Feb.17 James

1810, Jan.14 Sam died 1834 aged 25.

1812, Mar.I Sarah

1813, Sep.26 John

1815, Oct.I Thomas

1817, Mar. 9 Jesse

1818, Aug.16 Stephen died 1839 aged 21

1824, Mar. 21 Edward died 1827, aged 13

The marriage of William Barnes and Harriet Rofe (Roaf, Roffe, Roff) is recorded November 25th 1825 in Cranbrook, Kent.

The following are the baptismal dates of their family

1827, Oct. 14 William Robert

1829, Nov. 22 Harriet Ann (named after her mother and grandmother.)

1831, Mar. 13 Francis

1834, Nov. 17 Caroline Buried Oct. 2 1836, aged about 2 years

1835, Dec. 25 Hannah

1838, Dec. 16 Ann Died Nov. 3@ 1839, aged about I year.

1840, Oct. 18 Thomas Died at sea during the voyage to New Zealand 9th July 184l. aged 8 months,

In the census for Cranbrook taken June 12, 1841 the following entry is shown: -

Location Name Age Trade

Carriers Yard William Barns 35 Blacksmith

Harriet 35

William Robert 13

Harriet 12

Francis 10

Hannah 5

Thomas 8 months

Note: Barnes has been spelt variously in the records.

William Robert aged 13 years - above - was shown as a labourer aged 14 yrs on the shipping list to New Zealand. He may have been nearly 14 by then but ages were sometimes advanced a to qualify as labourers or domestics.

The Emigrants.

William Blunt Barnes

William Blunt Barnes was born March 20 1803 - the son of William Barnes and Ann Blunt.

He died March 3, 1883, at Wellington, NZ, and was buried in the Karori Anglican Cemetery, Wellington.

Before he left England, William had married Harriet Roff (Roffe, or Roaf), circa 1826 – 7, and had four children.

The name of William Barnes appears on the "Register of Emigrant Labourer applying for a Free Passage to New Zealand", "Public Record Office, London." (Copy held by Turnbull Library, Wellington).

The "Application made to and accepted by E.H.Mears 17 May 1841, no 3118: "William Barnes, blacksmith and his wife Harriet, both aged 36, I boy 7 months, 3 girls 12, 10, 5 I/2. Place of residence Cranbrook.

No 3119 on the Register is William Robert Barnes, labourer, aged 14, also from Cranbrook. This lad was the eldest child of William and Harriet Barnes.

William and Harriet Barnes with their family arrived at Port Nicholson on the 3rd November 1841 on the passenger ship "Gertrude". This ship of 560 tons register had left Gravesend in June 1841 and was commanded by Capt. T.F.Stead. The couple brought with them three children. The youngest son, Thomas, had died at sea 9th July aged 8 months.

Extracts from Early Wellington Electoral Rolls held in the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington: -

Barnes, William - Parkvale, Karori. Settler. Freehold (1853, 1857, and 18556)

Barnes, William Blunt, settler. Dwelling Dixon Street, two properties

£28 rateable value}

£25 rateable value} 1882

William Robert Barnes

The following extracts from the Electoral Rolls refer to the son William Robert Barnes

Barnes, William Robert, Park Vale, Labourer. (1852)

Barnes, William Junior, Park Vale, Karori. Settler leashold (1855, 1856, 1857)

Barnes, William Robert, Dixon Street, Freehold, house on 170 (appears in 1867, 1868, 1869, and 1870 rolls)

Barnes, William, Hutt (place of abode). Dixon Street house and land (1868, 1869, and 1870)

This last entry could refer to William Robert as above. He took labouring contracts and at one stage was working on the construction of a road from Wellington to Petone. He spent some time at the Hutt.

The Family of William and Harriet Barnes

William

Robert. Born

16/9/1827, in Kent, England

Married Sarah Brandt (widow - nee Townley) who came from Preston, Lancashire,

26th August 1855.

William dies 27 Sept. 1922, and was buried in the Karori Anglican Cemetery, Wellington.

Francis Born ?

Married J. Fry (?). They had one daughter, who married ? Knight who settled in the Manawatu.

Harriet

Ann

Born?

Married ? Oakley and resided in Canterbury (name from her father's will)

Thomas Died at sea during the voyage to New Zealand, 9th July 1841, aged 8 months.

There was a third daughter mentioned in the "Register of Emigrant

Labourers". She was given as 5 I/2 years, but we have no record of

this child, and she was not mentioned in her father's will. Presumably

she must have died as a child if the list is correct. The census list

gives this third daughter, Hannah, 5 yrs.

Sarah Barnes, as a young woman, and an old lady.

The Family of William Robert and Sarah Barnes.

John

Born

31/6/1859, Karori, Wellington.

Married

24/11/1881 Hannah, daughter of John and Mary Jane Old

Died

10.6.1925, Wanganui (Fordell). He was buried in the Anglican Cemetery at

Matarawa, near Fordell.

Harriet Francis Born 25/5/1856,

Married Thomas Cole

Died 8/9/1938

William Robert, like his father, was a farmer and in 1867 he was farming a property in Owhariu which is about nine miles by road from Johnsonville, via the old Porirua Rd. In his work he associated with the Maori people and become proficient in their language. As a result he was occasionally called upon to act as interpreter in the law court. He often travelled up the coast visiting the Maori villages and buying pigs for sale on the Wellington market. His knowledge of the Maori language was put to good use.

In his later years after his wife had died he spend a lot of his time with his son John at Mangamahu, though he made his home with his sister Francis at Karori or at their town house at Thorndon. William Robert had a long active life and was 95 when he died.

The first

generation born in New Zealand - John Barnes

|

|

John Barnes was born in Wellington in 1859. His education was extremely limited. It was before the days of free and compulsory education. One day after a few months at school he was locked in the classroom and forgotten by the teacher. Some hours later he was rescued by his father and he never returned to school. However, his mother had a fair education and he probably learned quite a lot from her, also when he became apprenticed to the building trade his boss, Mr Carter, saw that he had opportunities for learning. He became quite proficient in the calculations necessary for his trade and also became a keen reader. He made quite a success of his trade of building. As part of his apprenticeship he spend a year in the Sash and Door factory of Weddell, McLeod, and Weir. This experience stood him in good stead years later when he was building houses in the Fordell District. He was able to do all his own joinery and build a house from the foundations up. Also during his training he gained experience in shingling roofs, and on one occasion was loaned by his boss to another builder to renew the shingles on a church spire.

For some time he worked at his trade in Wellington and on construction work on the Rimutaka Railway, but left that to take up work in Wanganui. However, the slump of the late 1870's meant that no work was available and he went out into the country to do any labouring work offering. This was usually ditch and bank fencing. While working in the Fordell district he met his future wife, Hannah Old, and also his future partner in the building trade, Mr Richardson. The firm of Barnes and Richardson was carried on for many years by both Mr Richardson and his son Marton.

About 1983

John Barnes took up a block of land in the remote Mangamahu district.

This land was developed between building jobs by himself and his family.

In 1907 he sold out to a neighbour and came to live at Fordell where his family

had a better chance of receiving an education. Here he supplemented his

building by a carrying business.

As a result of an accident in

the harvest field, his last ten years were marred by ill health.

|

|

|

|

|

The

Barnes Family, about 1916

Photo taken when George and Albert were on final leave, World War I, about 1916.

Back row: George Barnes, John Barnes, Beatrice Gould, Bert (Albert Lewis) Campbell, Olive Barnes, Arthur Cyril Barnes

Second row:- Albert Barnes, Jessie Barnes (Later Mrs R. Campbell), John Barnes (father), Hannah Barnes (mother), Frances (Mrs A.L.Campbell), Jessie Campbell In front: Eric Campbell, Ken Campbell, Victor Barnes

Absent: Maurice Barnes (overseas) |

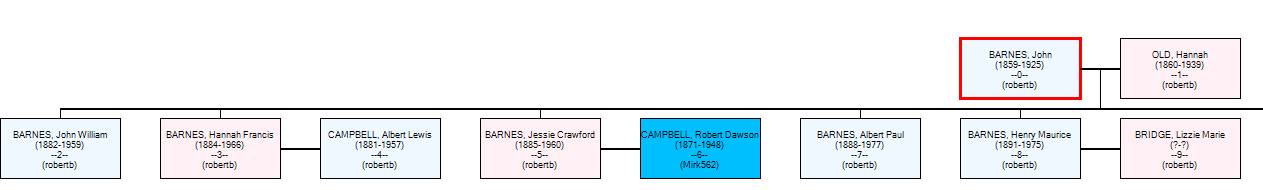

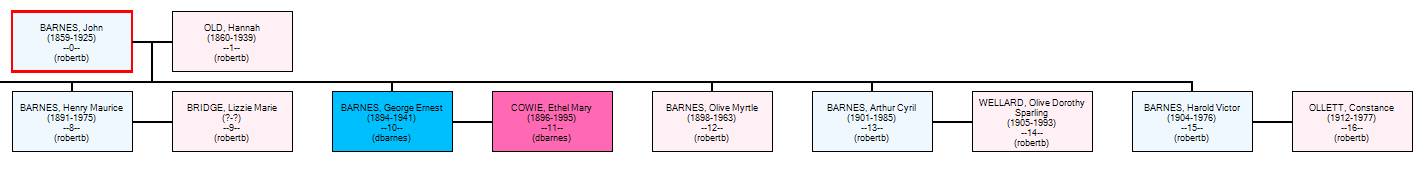

The Family of John and Hannah Barnes (nee Old)

John William Born Wanganui 6/9/1882, Died Fordell 11/I/1959, unmarried

Hannah Francis Born Wanganui 22/5/1884, Died Wanganui 4/3/1966

Married Albert Lewis Campbell,

2 sons, one daughter

Jessie Crawford Born Wanganui 18/12/1885, died 11/5/1960

Married 10.5.1960 No family

Albert Paul Born Wanganui, 6/12/1888, died ??

Unmarried

Henry Maurice Born Wanganui 8/5/1891, died Greytown 1975

Married Lizzie Marie Bridge, 1 daughter

George Earnest Born Wanganui 26/I/1894, died 8/3/1941

Married Ethel Mary Cowie. 2 sons

Beatrice Emma Gould (Neice) m. Henry R.D.Campbell. 3 sons

Olive Myrtle Born Wanganui 14/12/1898, died 7/3/63. Unmarried

Arthur Cyril Born Wanganui 13/11/1901.

Married Olive D.S.Wellard. 2 sons.

Harold Victor Born Wanganui 21/9/1904, Married Constance Olett, 1933.

I son, three daughters.

(Inserted by R. Barnes, 2012): -

Here is a descent tree of this

couple (I couldn’t fit it on one page, even reducing its scale and restricting

it to one generation, without it becoming unreadable): -

The Family of Thomas and Francis Cole (nee Barnes)

John Married Elsie

Thomas Married L.Hall

Horace Married E. Bayliss - 3 sons, 2 daughters

Ernest Married R. Allen I son, one daughter

William Killed 1914-1918 war

Elizabeth Married Oliver Old (brother of Hannah Barnes)

3 sons, 5 daughters

Amy Married A. Parlane 3 sons, I daughter

May Married E. Tucker I son, 2 daughter

The Next Generation - the descendents of John and Hannah Barnes

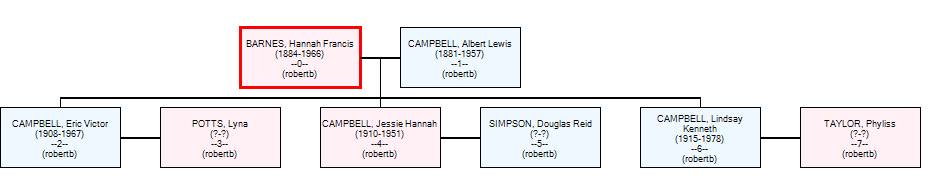

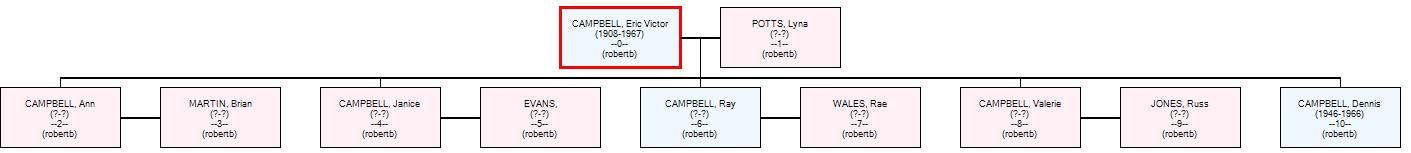

The Family of Albert and Francis Campbell (nee Barnes)

Their family: -

Ray m. Ray Wales ? sons

Valerie m. Russ Jones 2 sons

Dennis (killed)

Ann m. Brian Martin ? sons

Janice m.

Evans

I daughter

Lindsay Kenneth m Phyliss Taylor 2 daughters, I son.

Lachlan married, no family

Donald unmarried

Heather m Barry Hodson 2 daughters

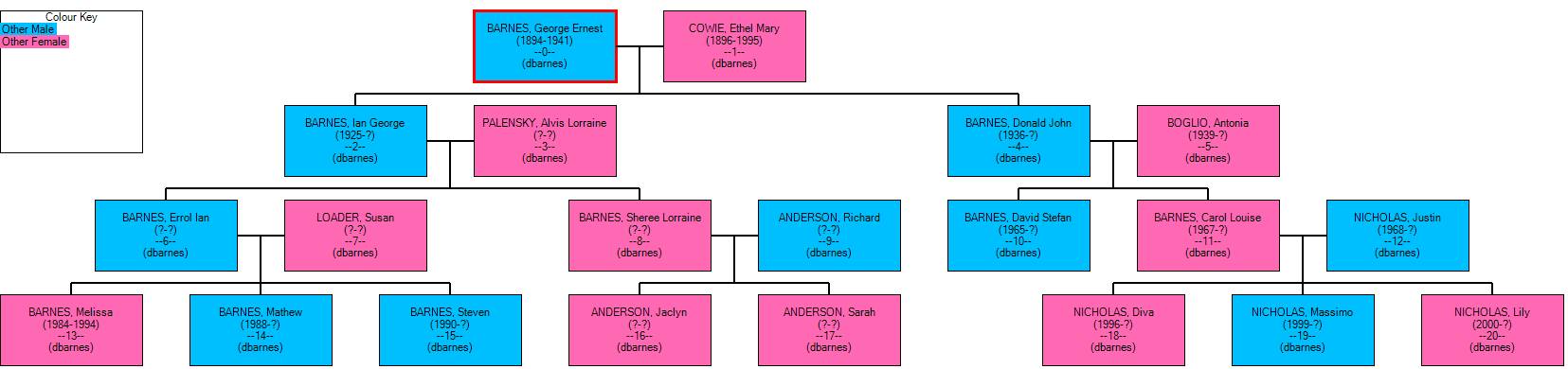

The family of George and Ethel Barnes (nee Cowie)

Ian George m. Jacky Peters (nee Polanzki)

Errol

Cherie

Donald John m. Antonia Broglio

David}

Carol} Adopted

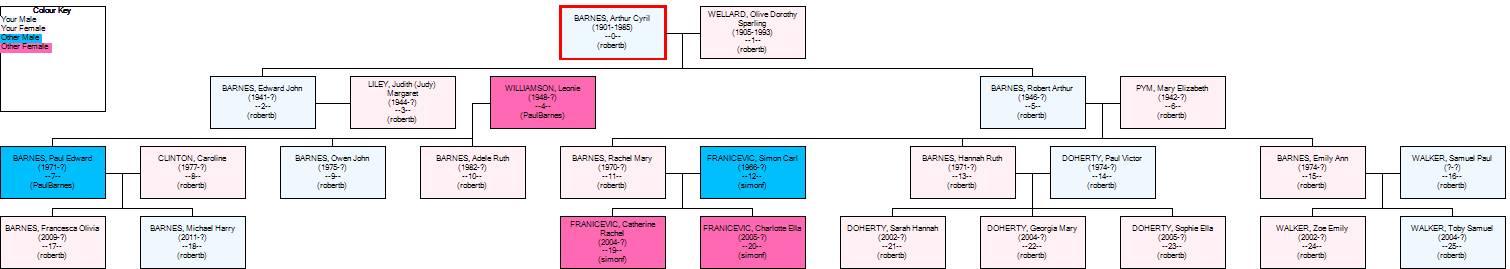

The Family of Arthur and Olive Barnes (nee Wellard)

This couple were married 9th Mary 1933, at the residence of A.E.Wellard (42 Liffiton St., Wanganui).

Refer to The Wellard Story.doc for the story of Olive Wellard.

Two Sons: -

Edward John Born 5th June 1941 m. Leonie Williamson 7th Dec 1968 at Newcastle, NSW

Family

Paul Edward b. 23 Dec 1971

Owen John b. 23 Dec 1975

Robert Arthur Born 28th May 1946. Married Mary Pym, March 22 1969, at Auckland, NZ.

Family

Rachel Mary b.26 March 1970

Hannah Ruth b. 21 Dec 1971

Emily Ann b. 31 Oct, 1974

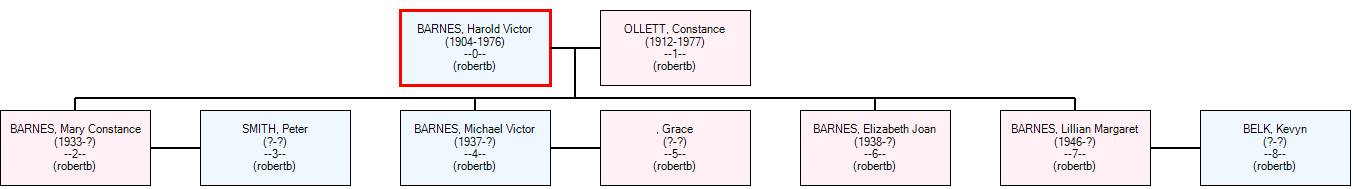

The Family of Victor and Constance Barnes

Mary (Molly) m. P. Smith -- 2 daughters, I son

Elizabeth (Betty) Unmarried

Michael m. Grace 1 son

Lillian

m. ?? Belk 1 son, 1 daughter

Maurice and Marie.

The only information I[1] have currently is: -

Barnes, Henry Maurice Born:6/05/1891 (Wanganui) Died:1975 (Greytown)

married to Bridge, Lizzie Marie. 1 daughter.

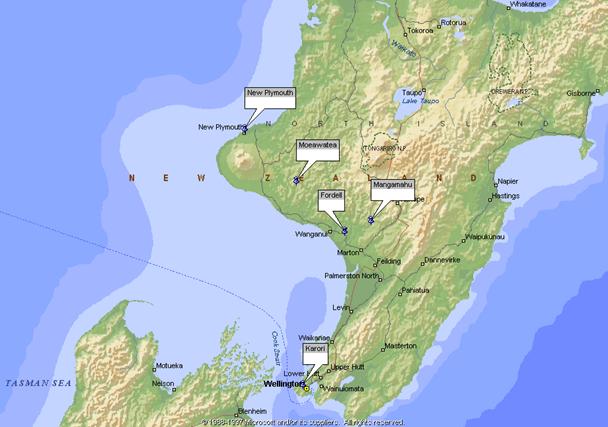

New

Zealand Localities.

Family History

and Early Recollections

A.C. Barnes, 1965

At this distance in time, after a century and a quarter, it is difficult to find out just what was so compelling to the English working people that they gave up their homes, thus traditions of centuries, their comparative security, to emigrate to an unknown land whose inhabitants were known to be warlike and savage, however "noble" some travellers had proclaimed them to be. We know, of course, that the weather cycle had caused a series of bad harvests; we know, too, that the oppression of the workers by the land owners was at times harsh, because, to keep up their facade of fashionable show, the gentry needed more and more in returns from land that seemed to be producing less and less, for the agrarian revolution had not yet been the accepted form of production. But we do not know what was the final spark that exploded the discontent with the prevailing conditions, that scattered country folk from places as far apart as Kent and Cornwall, to suddenly take up their roots and go half way round the world to transplant them again. The agents of the New Zealand Company must have been very persuasive, with an ability to paint a glowing picture of the opportunities that a new land offered. Whatever the causes, the results were concentrated settlements of British people, mostly English from the southern and western counties who came out expecting to find a new heaven, although they knew that strenuous work was needed in the finding of it. The classes of society then prevalent in England, from the well-to-do adventurer to the poor and humble labourer, were all fairly well represented. But the labourers were able, by acquiring a few acres of land "bought" from the Maoris, to shed much of their dependence upon their former employers, and set themselves up as independent farmers, to flourish or starve according to the smiles or frowns of fickle fortune.

One of these "lower orders" was my great-grandfather, William Barnes, a poorly educated farm labourer from Kent. Just which part of Kent he came from I have never been able to find with any certainty. The names of Tonbridge and Seven Oaks have been mentioned by the older members of the family, but with only vague references. My father told us that the land owner his grandfather worked for had several estates in different parts of the county and sometimes the workmen were required on one or another estate. Also I have heard my father say that the estate that his grandfather worked on as a labourer had originally belong to his grandfather, that is, two generations before. With the uncertainty of conditions at the time of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, it is possible that the family had lost its position. It is certain that William Barnes was not in any influential position, although his father is reported to have been sufficiently educated to be a parson. When the family left for this country it consisted of William Barnes, aged 36, his wife Harriet also aged 36, and four children including William Robert, then a boy of fourteen. Of the other children one, Thomas, died on the journey out (aged eight months). The other two were girls. We have lost all trace of one of these daughters. Some years after coming to New Zealand she married and went to live in the South Island. But as neither she nor the other members of the family could read or write all contact has been lost.

The other daughter married a settler in the Hutt Valley. We always understood that his name was Joe Fry and Dad always referred to "Aunt Fry" when speaking of her as it was customary to refer by the surname instead of the Christian name. Occasionally she was "Aunt Frances Fry" and even though he had no other Aunt Frances the surname was always attached. A trace of the same custom lingered into our own generation when an aunt referred to herself in a letter to me as "your Aunt Old."

The Fry family consisted of one daughter who married a man by the name of Knight and moved to the Manawatu area when that district was first opened up. This cousin of my father's in her old age lived at Newbury near Paimerston North and on several occasions my mother visited her. I do not know which of the many Knights in the Feilding district were her descendants, but I always had an idea that Sam Knight whom we knew well at Apiti was one, and was my second cousin.

When the Barnes family left Gravesend in June of 1841 they were on the ship "Gertrude" of 560 tons, whose captain was T.F. Stead. This ship arrived at Port Nicholson on November 3 of the same year after a passage of just over four months, and the passengers were disembarked on the Britannia beach, to be housed in temporary primitive accommodation until an allocation of land was made to them. When this was eventually done, they found that their new farm was in bush, as practically all the land surrounding Port Nicholson was, in a locality which was reached by walking along to the mouth of the Kaiwharawhara Stream, then upstream for about a mile and over the high range of hills, to bring them out to a valley behind what is now Karori. Later this area, known as Park Vale, was linked by a road over the hill to Karori, and, as the settlement grew, this route was the usual way into Wellington, when the town was established on the Lambton Harbour.

Besides the farm property there was also a town section, somewhere in the vicinity of Tinakori Rd. I know that some of the time that my father was a small boy was spent at a cottage in Glenbervie Terrace, but whether that was the original allocation is now unknown.

Very little is known now of William Barnes or his wife Harriet. The few stories that have come to us suggest that he was rather short-tempered and also interferingly inquisitive. It was told of him that, on one occasion, he was seen approaching Bowater's Blacksmith shop and so young Bowater the blacksmith who had been making a slasher dipped the red-hot implement in the water - but to blacken it off, placed in on the bench where it was obvious, and then pretended to be very busy with something else. In came William Barnes, saw the apparently finished slasher head and immediately went over and picked it up. It was still hot enough to burn quite a sore patch on his hand, whereat he dropped it suddenly and rounded upon the young blacksmith. "You did that on purpose! You knew I would pick it up!" he is reported to have said.

He must have been a reasonably good farmer who could adapt his English farming practice to the conditions in the new country as he seems to have made a fairly good living. When he died he left some property and money which he left to his daughter, the Miss Fry mentioned above. The son, William Robert B. was apparently cut off with the proverbial shilling.

Of William Robert, we have a more extensive knowledge. He was a lad of fourteen when the family arrived in New Zealand, Even at that age he had served a thorough apprenticeship in English farming and horticultural methods. I have known few people who had his ability with fruit trees particularly the bush fruits such as currants and gooseberries. At our farm in Mangamahu many years later he kept the orchard in order, and in no other place have I seen gooseberries growing on long stems like standard roses. It certainly made the fruit easy to pick.

William Robert Barnes was a small man. As I knew him he was a frail old man of advanced age, but many stories were told around the family, of his feats of strength and endurance. As a young man he sometimes made trips into the lower Manawatu where he bought pigs from the Maoris to drive to Wellington when he would sell them. When work was to be had he was sure of employment, but he felt his lack of education. His association with the Maori people made him a fluent Maori linguist. On one occasion he was called into the court to act as interpreter to some of the local natives. The official interpreters knew the standard Maori language but were not conversant with the local variations. When he suggested an interpretation of a disputed matter, his translation was immediately accepted by the local Maoris. The result was that he was offered a permanent position, but he felt that he couldn't accept because of his inability to read or write.

His contacts with the Maoris were not always so acceptable to them. On one occasion he found an old Maori on his land gathering fungus. The Maoris had just discovered that they could sell this to the Chinese, of whom there were a few in the country. When he found the Maori on his property he at once wanted to know what he was doing. He could see what the Maori was gathering and wished to know the reason. But the wily old native didn't want to give away his secret source of revenue, so replied, "Make it te kail' (food).

"Right," said grandfather, selecting a slobbery piece of fungus, "you eat!"

"He no cook," wailed the Maori.

"Cook or not," was the reply, "you eat!"

And, because grandfather was armed with a long-handled cutting knife, the Maori was forced to eat, however unpalatable the fungus may have been.

One day, when racial feeling was running pretty high, grandfather was working in his garden, and happening to look up, noticed a fern across the gully where a fern should not have been. So he quickly stepped around an old stump to get his gun, but on his return he found the fern had disappeared.

When the first road was being made between the settlements at Wellington and Petone, grandfather was engaged for part of the time as a labourer. On one occasion his gang had set a charge of explosives to blow the rocks from one of the points and had just retired to a position of safety when to their consternation, they saw a party of Maoris come and stand just where the fuse was fizzing towards the charge. They yelled warnings, but the Maoris did not understand. Presently there was a loud explosion, rocks, dirt and people went flying skyward but fortunately nobody was hurt. The road gang were able to explain the situation so that no damage was done to the racial relations but that sort of situation was liable to start a local war in those times.

William Robert Barnes married the widow of a sea-captain, a Mrs. Brandt, who was originally Sarah Townley of Liverpool. Her people were in the jewellery trade but by backing a bill lost most of their substance. The Captain Brandt was killed at the dockside in Sydney. Presumably his death was due to an accident but some doubt always existed that a captain would fall between his ship and the wharf.

Mrs. Brandt had one son, Paul, in her first family and a son John (my father) and a daughter Frances in the second family. Paul, when he grew up, learned the trade of pastrycook and baker, and for many years worked for Godber's in Wellington. Years later he went to Australia and in Melbourne took a prominent part in Trades Hall affairs. He wrote on many aspects of the labour situation and a small pamphlet of his on proportional representation in elections set out a scheme of voting very similar to the one used in the Australian elections today. He never married. We occasionally heard from him, at first from letters he wrote to Mother and later through George with whom he corresponded. He gave all of the brothers who went to the 1914-18 war letters of introduction to relatives in England, and it was through such a letter that my brother Maurice met the girl who came out to be his wife, Marie Bridge, a distantly related cousin.

Living with William Robert Barnes must have been frustrating in many ways. He was, in common with numbers of his contemporaries, a hard drinker. At times, Dad has said, he was scarcely sober for days on end. In spite of appeals by his wife to give up his drinking he persisted until her death, when he suddenly broke with his past and, as far as I can find out, did not drink again. It is a pity our grandmother never knew the satisfaction of knowing the change in him.

She was a good woman, supporting her church and bringing up her family in the Christian ways. Her people in England were Methodists and she when possible worshipped with the same people in New Zealand. Two of her old hymn books I was able to give to the Turnbull Library. There seems to have been a close association with the Church of England too. My father always paid allegiance to that sect, but I know that his "boss" was an Anglican and when Dad lived with him, as the custom then was for apprentices, he was expected to attend the master's church.

Of my grandmother I know very little. She had died before I was born. Grandfather, on the other hand, was living with us when I was small and the fleeting childhood memories suggest a kindly old man who used to take me on his knee and tell me stories of his young days. I would give much to have remembered those stories, as the age they reflected was already going, and is now so far away that it is history. I do not know how long he lived with us, but I know it lasted for some years. I have a faint recollection of the day he left to go to Wellington to live with his daughter, Aunt Frances, and, except for an occasional holiday at our place, he never came to live with us again. At that time Aunt Frances had lost her husband, most of her family had married and had their own homes, so that there was no shortage of room for the old man.

I have much more vivid memories of him in his last year, as I was a student at the Wellington Teachers' Training College then, staying with my cousin Mrs Burne in the same suburb of Karori. Quite often we would go up to Aunt's place (she was "Jim" Barnes's mother) and in the daytime old Grandfather would be sitting out by the wood heap. He would saw and split the firewood and then rest a while. On cold days he sat by the stove in the kitchen. But at ninety-five he had lost his briskness that I remembered from the earlier years. Occasionally he would recount some old happening, but those around him would usually laugh at him and say, "Oh you don't want to take any notice of what he says." And that was a pity because I was eager to listen.

When he died he was buried in the church yard at St Mary's Church, Karori, with many of the old pioneer families of Karori and Wellington represented at the funeral. Even though his grandson, I was a stranger.

My father, John Barnes, grew up in the Karori district. He had practically no formal education. Some of the time he spent with his grandparents on the Parkvale farm. For the rest I know little. Some of the time the family live in "town", but the main part was in the country. He started school at an early age but when he failed to come home after school one night, his father drove up to the school, found he had been shut in the school, and rescued him through one of the windows. That was his last day at school. In those days there was neither free nor compulsory education. If the children did not take their shillings to school on Monday morning they were sent home again. So the defection of one small pupil would not seriously affect the school or the schoolmaster.

What little education Dad received was incidental to his apprenticeship. In that respect he was extremely fortunate. At the age of fourteen he was indentured to a builder by the name of Carter. Mr. Carter must have been a very conscientious man and an excellent tradesman. For five years, until his apprenticeship was finished, Dad lived with the family. Mr. Carter was better educated than many of the artisans of his time, and encouraged his apprentices to better themselves. He had a number of books which they were encouraged to read and in other ways saw to their advancement. Every aspect of their trade practices was catered for, and their social well-being was keenly watched. An instance of this is shown by this action. For the first week there seemed little for my father to do and several of the men used to have him turning the grindstone so that they could sharpen their tools. Even to a grown man this can be a backbreaking task; to a boy of fourteen it was a burden. When he became slow through weariness one of the men savagely kicked him to make him turn faster. Immediately Dad reported the incident to his "boss" who straight away dismissed the workman. If there was any punishing to do, he said, he would do it himself.

Little scraps of life in those times read like the days of the "wild west". The 'prentice lads were always ready for mischief, and some parts of the town were noted places, to be avoided at all costs if possible. One such place was Courtenay Place. It was then lined on either side by timber yards, and at nighttime was poorly lit. The boys used to haul out the baulks of timber and lay them across the roadway. Then, when the horse-drawn carriages came along to a theatre or reception they would get a very rough ride. "Many a carriage wheel I have seen broken," said Dad, "and many a horse brought to its knees." Even the police avoided this trouble spot. "There was only one policeman who could handle the lads. He would go along and say 'All right boys! Put it away and go home!' And they would do it. But if any of the other police came along and tried to bounce the lads he would probably be laid out."

When I remember some of the stories Dad used to tell of the pranks the young people indulged in, I am certain that today's delinquents are no worse. Today's youth has instruments to hand that were undreamed of then, but respect for life and property has never been a characteristic of the irresponsible section of youth.

Part of the trade that appealed to my father was putting shingles on roofs, or "shingling" so he referred to it. Corrugated iron had not then become the universal roofing material that it later was in New Zealand, and most dwellings and quite a number of larger buildings had split wooden shingles to keep the roof water-tight. The method of overlapping and the steep pitch of the rafters gave almost a hundred per cent efficiency to this type of covering. A good man could do a hundred square feet in a day, so that the work was generally taken on by specialists. On several occasions my father was "lent" by his boss to other builders who required the services of an expert. One of the jobs he did was the roof of the steeple of St. Pauls. This he enjoyed as it gave him a chance to do work that doesn't come the way of every apprentice. He was slung from a bosun's chain, much as the sailors are when painting a ship. Also, he received journeyman's wages on these outside jobs, which was more than his articles entitled him to.

On completing his apprenticeship he went into a joinery factory working for the firm of Wardell, Weir and McLeod. Here he was making doors, sashes, frames and other fittings, knowledge so necessary for any builder doing country work away from the fitting factories available to the town builder. Then he took work with a contractor who was putting up the buildings on the railway being pushed through from Wellington to the Wairarapa. He has told of his work at such places as Pigeon Bush and Cross Creek. For the greater part the buildings were the goods sheds, and, in contrast to the joinery factory work, the men were using large sized timbers. Flooring was laid in the rough and trimmed with adzes. The men lived together in large bunk-houses under most primitive conditions.

This work did not last long as the contractor and Dad found it difficult to get along amicably. So he left, and, after a brief turn in the pattern-making shop at the railway workshops, left for Wanganui where he had been promised work making furniture.

On arrival in Wanganui he found that the ruling wage was lower than he had agreed to come for, and in a short while he was working at whatever job was available. This was at the beginning of the great slump, and gradually employment in the trades ceased. So he went out into the country. Many of the farms still needed cottages and sheds and to these he turned his hand. By working long hours he could build a two-roomed cottage in a fortnight, from foundation to finish, including sashes and doors. And provided the timber was supplied there was little more than his wages in costs to the farmer.

At last even these small cottages were beyond the resources of the farming people, and, when wages at the building trade fell below ten shillings a day he refused to work at his trade for less than that. So he took up all classes of country work from harvesting to fencing. The usual type of fencing then was ditch-and-bank, two shallow ditches or trenches being dug and the sods piled on to a central bank. This gave a height of about three feet to four feet, which was sufficient to keep the stock in. With a work-mate, Charlie Circhetto he did many miles of this work mostly in the Whangaehu and Fordell areas. It was while doing this country work that he became acquainted with the Old family, living at that time in Denlair near Fordell. Hannah Old and he were soon very friendly, and on her twenty-first birthday they were married. Her father gave them five acres at the top corner of the farm and there they lived for thirteen years, and there the eldest of their children were born.

The Old family had a similar beginning in this country to the Barnes family, although their place of settlement was at first in Taranaki. When the people of Devon and Cornwall were being enticed to emigrate to the new country, two Cornish families w.ere included in the passenger list of the "Essex" a small ship of 329 tons and commanded by Henry Oakley. These were the families of Richard Old and his wife Jane, and Nicholas Knuckey and his wife Zenobia. In the Old family was a son John about twenty years of age, and the Knuckey family had a daughter Mary Jane. These were later married, one of the earliest marriages in St Mary's Church and lived for a time in or near the town of New Plymouth.

Two factors caused John Old to leave New Plymouth. One was the growing difficulty of earning a livelihood, for the bad times came early to Taranaki settlement; the other was the growing restlessness of the Maori people who resented many of the intrusions of the white farmers into the lands that had been traditional Maori preserves. This fear for the growing family became more acute, and so John Old left his wife and children in the custody of her people and set off to Wanganui where conditions were more amicable. His way lay around the coast, as the inland route was then known only to the Maori tauas, and his only accommodation was with the Maoris in their settlements. His only way of travelling was on foot, which meant that he was several days in reaching Wanganui. At one pa a guard was put on the doorway to his sleeping hut, not for his protection, but to prevent him from escaping. Knowing it was the chief's intention to detain and probably kill him, John Old rose stealthily in the early hours of the morning, stepped over the sleeping sentry, and was away before the other inhabitants realized he was no longer there.

In Wanganui he took up a tract of land near Fordell, but there was some dispute over the title and eventually he had to purchase another farm at Denlair, about four miles beyond Fordell. Here the turbulence of the inter-racial conflicts was not so evident, and as soon as a house was ready the family was sent for, travelling by ship from New Plymouth to Wanganui. It is recorded a ship, "Mary Jane" of 40 tons in 1855 had as passengers Mrs Old and four children, returning probably to visit anxious parents and relatives in New Plymouth. The fact that she and the ship both bore the same name was probably a co-incidence to be commented upon.

Among the children born to the Olds in Wanganui was a daughter Hannah, one of the younger ones. She was born in Wanganui on November 24, 1860. She grew up on their farm at Denlair, receiving her education at a tiny school, the forerunner of the Denlair School, situated near where the hilly section of the No. 2 Line begins at the place we know as Sutherland's Hill. There was a road surveyed from Denlair to this place, but it was never more than a track through the bush and scrub. When I was a youngster, much of it had become overgrown with gorse. I have an old school inkwell that was dug up near the old school site when some excavations for road or quarry work was being done there.

Hannah Old seems to have been a promising pupil. The highest class in the school was Standard four, and this she attained. Years afterwards she had no difficulty in doing primary school work to help us even in the sixth standard. She always worked out quantities and estimates for her husband when he was preparing a building tender.

1do not know any person to whom the term lovable could better be applied. That was her chief characteristic. If anybody in the family or the district was in pain or grief, she was the one to turn to. She was practical, particularly in case of sickness and accident, but her practicality was hidden in her sympathy so that she was consulted before a doctor was called in most neighbour’s homes. In some cases she could do as well as a trained nurse or even a doctor, and later, when the family moved into the backblocks this ability to treat and cure the common ills caused demands upon her services at all times of the day or night.

From the marriage of John Barnes and Hannah Old came the family of second generation New Zealanders. The eldest of their family was named John William, after his father and two grandfathers. Then came a daughter Hannah Frances, known by her second name, which had been a traditional one in the Barnes family. The third child was also a girl named Jessie Crawford after a great friend of the mothers. From then on the names seemed to be chosen without reference to any earlier relative on either side - Albert Paul, Henry Maurice (also known by his second name), George Ernest, Olive Myrtle, Arthur Cyril and Harold Victor, the last two also know to the family by second names. In addition to these nine children the family was augmented by a small cousin who, at the age of three years lost her mother. This was Beatrice Gould whose mother Christine, was a younger sister of Hannah Barnes. So in a practical sense there were ten of us.

The older members of the family began their schooling at the Denlair.School not the one their mother had attended, but one built in the middle of the settlement, and still in use until about 1940 when it was closed and sold to one of the local farmers. The contract for the building of the school was carried out by John Barnes. Frances, Jessie, and Albert were eager pupils, but John was slow, and often his stubbornness arose to hold him back. Also he had the family fear of examinations, which, in the days when all promotions depended upon an inspector's examination, meant that his progress through the school was slow. When, in 1893 the family took up a bush farm beyond Mangamahu John had reached only Standard 2, which was all the formal education he ever had.

Frances, Jessie and Albert were left at Denlair with relatives to continue their school classes and were much better prepared. The younger members of the family were at first schooled at home. Dad built a schoolroom in a paddock behind the house and in it Frances taught the younger ones - Beatrice, George, Maurice and Olive. Vic and I (Cyril) were not of school age when we left the district. Later a Board school was built about a mile down the road, and all of the children (our own and our neighbours') who had attended the household school went to it.

In 1907 the farm was sold and the family went to Fordell to live. After a few months in the school house we moved into the home Dad had built. Here has been the family headquarters ever since. Living closer to a large centre gave opportunities for secondary education to us younger ones that the older ones did not have. Maurice finished his primary education at Fordell and then went to work. He had much of John's stubbornness, and at school he did not show to advantage. George, on the other hand, learned readily and after completing his primary schooling went on to secondary school. Travel arrangements for this were difficult. At first the only school to which he could travel was the Marton District High School. This meant leaving home before eight every morning and getting back after six in the evening. For three years he did this. Then a local group of people from Fordell, Wangaehu, Okoia and Turakina prevailed upon the Railway Department to put a carriage on the early goods train from Marton to Wanganui, so that the children could travel to the larger schools in the nearer town. So we younger ones, Olive, then I and then Vic were to benefit by their pioneering efforts, and all in our time became pupils of the Wanganui Technical High School, usually known as "The Tech".

At Fordell John Barnes once again took up his trade of builder (he had always done some building work, even when he was farming). But there wasn't enough building in the district to give him full time employment and he had to do other work. For the first few years he drove a team of horses in a light wagon to Mangamahu, taking in supplies and bringing out wool. He had invested the money from the sale of the farm in another back-blocks farm, this time in the Moeawatea Valley beyond Waverley. The two eldest boys John and Albert ran the farm and developed it. It was not a good arrangement. John was always the older brother and therefore what he wanted to do was done and it was not always the best thing to do. He was always very good to his neighbours, often to the neglect of his own place. Some of his ideas were somewhat hare-brained. The result was that Albert found it very difficult to work with him. Expenses connected with the clearing of the land, purchase of stock, losses especially of cattle in the gorges, all make depressing items to record. Then came the 1914 war and the expeditionary forces for overseas service. Albert and George, who was then at Teachers' Training College, went away with the 17th reinforcements. Maurice had already gone with the seventh. John was left to manage the farm alone. For years it seems, more money was put into the place than came out of it. A godsend was the shilling-a-pound price guaranteed by the British government for the wool, which was in such demand for the making of uniforms.

On the day that George and Albert left New Zealand to go overseas, Dad met with a serious accident. There never was enough work in the country to keep him at his trade and so he took what was offering. So many of the farm workers being drafted to the army meant that all hands who could help in the seasonal work were called upon to do such things as harvesting, and because Dad was used to handling horses, he was always sure of work in the flush of the harvesting season. He was working for Mr. H.G. Lewis driving a dray which was loaded with pressed hay, when the horse stumbled, throwing him from the load in front of the dray, so that the wheel went across his chest and head. He was taken to the hospital in a critical condition and not expected to live. The only person to give Mum any comfort was a catholic nun who assured her that Dad would live. After many anxious days he began slowly to recover and lived for nearly ten more years. But the accident put an end to his working life, except for an odd day now and again.

So that meant that there was very little coming in to the house. I was at the Wanganui Technical High School at the time, and I know it was a desperate struggle to provide me with books, clothing and other necessities. We had a couple of cows, and Mother made butter and sold it. Some of the vegetables from the garden were sold, too, but the income was small. George and Albert made over to Mum their payments from the army pay. The neighbours were very good, and while J. P. Cowie was in the store he was prepared to extend credit to the family. But unfortunately he was not there for long and Mother had to arrange with tradesmen in Wanganui for our necessities.

When the war ended and the boys came back home Albert again went back to the bush farm and George to his teaching. But the farmers of the country soon had financial difficulties to face and in about 1922 John and Albert walked off the farm, one of the neighbours agreeing to take it over.

With difficulty the family persuaded Dad to accept the old age pension and there was at least something to buy the groceries with. Mother kept a few boarders, mostly fine young men, and that also brought in a little. In January of 1925 I persuaded Mum and Dad to let me "shout" them a trip up the Main Trunk to visit various relatives. We stayed about a fortnight with Aunt Martha (Kurth) at Pukeatua. Then on the way home we stayed at Te Kuiti with Uncle Will Old and Aunt Emma, and from there we went for a few days to PioPio where Uncle Jim Old had a small farm among the ragwort. Our next stop was at Utiku to visit Mum's oldest sister Aunt Jane, Mrs John Doole (senior) and her husband. Uncle John Doole had come to New Zealand with the soldiers in the Maori Wars. First, his regiment went to India for the Mutiny, and then on to this country. He was present at the Battle of Orakau, the last stand of the Maoris under Rewi Maniapoto.

When we arrived home Dad went to bed and did not get up again. He died on June 10, 1925, of a cancer probably caused by his accident in the harvest field nearly ten years earlier.

Mother lived for another fourteen years, passing quietly away on the day war began in 1939. In her later years she had slowed down. At one stage, in 1927 or 28, she had a shock over the death of Maurice and Marie's kiddie and we did not expect her to recover. But she did. In the end she died at 78, her trouble as Doctor Anderson put it, was 'Three score years and ten". She had had a strenuous life, never free from worry and anxiety. Daughter of a pioneer she herself helped to pioneer the opening up of the back country where only the sturdily independent could survive.

At Mother's death the old home was bought in by Albert and the older members of the family. Jess had lost her husband soon after and so she, John, Albert, and Olive lived together until Jess, John and Olive died. Olive, John and Albert never married. At the present time Albert lives there alone. He is about 76. Maurice and Marie are just across in their home about half a mile away, Bert and Harry are still at Matarawa, Frances (over 80) is living by herself in Wanganui, although Ken, her younger son, has recently moved to Wanganui and is living at Springvale. Vic and his family are in Marton, while we are here in New Plymouth as also is Ethel, whose boys are married and away, Don and Antonia in Auckland, Ian, Jackie and family at Pungarehu. This is in 1965.

My personal story from the time I began work is very simple and straightforward. In 1919 I began teaching as a pupil-teacher at Queen's Park School. It was then only a couple of rooms that remained after the fire of 1917. Most of the classes were in various church halls in different parts of the town. After a month at the old school site I was sent down to St Paul's Hall to Miss Ross's Standard IV class. I have much to thank Miss Jane Ross for in the success I have had as a teacher. I have never met anybody so conscientious in her work. In some things she was too rigid and as a result she kept a stern discipline and was universally disliked by the youngsters. She was, however, respected by all. In my second year I was the headmaster's pupil-teacher, which meant that, with the head away to classes all over the town (there was also a side-school on St John's Hill) I was sometimes weeks at a time with the whole responsibility for the lessons and the general progress of the class. I remember one occasion when the head came in in a bit of a dither because he had heard that the inspectors were likely to come, and so he sat down and copied out from my workbook the work the class had been doing for the past week, an unheard of thing, as the pupil teacher was supposed to get his work-book notes from his head or class teacher. During my second year there were no classes in the old school, as the building was being demolished to make way for the new school on the old site.

In the years 1921 and 1922 I attended the Wellington Teachers' Training College. This was the usual procedure in those days. With very little knowledge of the opportunities that were there for university as well as teacher training I let slip the degree work, and it was many years later that I eventually took up studies to gain a Bachelor of Arts degree.

After my years at Training College I was appointed as assistant back at Queen's Park School, now a fine new brick building with accommodation for seven classes. But I had to take a class in a part of a corridor. I have never taught under worse conditions. Every noise from the classes was magnified by the brick walls and channelled to our end of the corridor. Added to that the Head (C.H. Warden) had frequent visits to our group as many of the youngsters were the "unteachables" who just stayed on at school because they had failed to pass their proficiency exams. However, I got on well with the youngsters and that gave me a liking for the "lower orders" a liking I kept to the end of my teaching days.

After the first year I had a regular classroom, and from then on I made average progress with my work. There were some who didn't do very well, but at the end of the year I received several letters of appreciation from parents, and felt that my relations with the kiddies must have been reasonably good. I know I was given a great deal more responsibility by the head than a junior assistant was usually given, because the first assistant who came about that time was most unsuited for his position.

Suddenly, after I had been at Queen's Park for over three and a half years, the Education Department realized that my appointment should have terminated at the end of the first year, so I was suddenly shot to a vacancy at Wanganui East, where I was again under C.H. Warden, who had moved there the previous year from Queen's Park. I was given a Standard I class at Wanganui East, eighty two of them. With a pupil-teacher I had to keep these kiddies working - it was tough, but valuable experience. I was just beginning to know the capabilities of the children when they moved up at the end of the year. I had applied for a sole charge position at Kiwitea but there was a hitch in the previous teacher's move, and I had to stay on at Wanganui East for another term, when I had a composite Standard IV/V class of very nice kiddies.

In May, 1927 I took over the Kiwitea school as sole teacher. I found the spread of the work rather daunting. However, I had a fine group of senior pupils who took over quite a lot of responsibility with the little ones and we got through the two years I was there with some credit, if the local reports were to be believed. I felt very pleased at the proficiency exam at the end of my first year when the inspector, Mr. Alec Crawford, took me aside and complimented me on the marking I had assessed to the kiddies. They were almost exactly the same as his in the exam.

In May, 1929, I returned to Wanganui as second (male) assistant at the Victoria Avenue School. Here I was put in charge of the Standard V boys, seventy three of them. They had had three months of relieving teachers and had got a bit out of hand, so for the first two or three weeks I had to be tough. By that time they knew what I wanted and we worked together quite harmoniously. There were one or two outlaws I was unable to tame, but most of the lads were just at the stage when a boy is "a lot of noise with mud on it."

My classroom was a corner room in a brick building and one day somebody said, "Earthquake!" We waited for a moment by which time we realized that it was a genuine quake, and so I stood the lads up and made them file quietly through the escape doors to the playground well away from the buildings. There we saw the full effects of the quake on the trees which were swishing noisily to and fro, and the overhead wires that were alternately taut or slack enough to loop half way to the road. Later we learned that the Murchison-Buller area had been the centre of things and great havoc was caused. We had a similar quake the following year when the Hawkes Bay disaster occurred. Fortunately the kiddies were still in the playground and no great alarm was felt.

The next year I was given a mixed class that was one of those classes a teacher always remembers with joy. Eager, happy, some brilliant, but all extremely likeable, these kiddies gave me one of the most memorable years of my whole teaching experience. I have had only four or five such years: This one at the Avenue School, three at Intermediate when I had the top stream of Form 2, and one (Standard 4) at Queen's Park when I was there as teacher-headmaster.

After three years at this school I suddenly found that the local educational plan was being re-organized and the Avenue School was to become the Wanganui Intermediate School with only forms I and 2 (which we had hitherto called Standards 5 and 6) and all of the central schools in the city were to close their classes with Standard 4. As I had done some art work beyond the usual primary school syllabus, I was appointed to the new intermediate school as art specialist, spending about half of my teaching time taking art with all classes of the school, and the remainder of the time teaching my "own" class English and arithmetic.

Our first Head was E. H.W. Rowntree who was the man to suggest that I study for a university degree and who helped me with Education and Psychology, subjects in which he was recognized as a specialist. The idea of intermediate schools was then new to us, and developed along very different lines from the ordinary primary schools. For the first few years there was a good deal of opposition, and from some people who should have understood the set-up better. In the end, however, the principle became accepted and now all areas with a school population to warrant it, seem keen to have intermediate schools, although there is still controversy over a two-year course.

After three years, Mr. Rowntree was appointed to the rectorship of Gore High School and we had Mr. H. Lochfort as our next head. He was a man of very different personality, but another man of great integrity as was Mr. Rowntree. Under him we developed the breadth of outlook that has since become the characteristic of most intermediate schools. Under these two principals I had classes of average progress in most years. It was not until later, when Mr Fossette became head and when I was appointed as first assistant, that I had the faster learners. My last three classes, made up of the "A" stream of Form 2 were perhaps the most spectacular of all my teaching experience. It was just a case of keeping the work up to the youngsters and their keenness was enough to set a cracking pace. They were very happy groups.

The time came, inevitably, when to gain promotion I had to move to the headmaster's position in an outlying school. This involved a move to Apiti where, in September 1946 I took over the school. Much of the work was new to me, especially the High School; but I had an experienced secondary assistant in Bob Gore and was happy to leave the senior work to him while I dealt with the senior primary classes where I had Standards three, four, five and six. Miss Greenwood had Standards one and two, while Miss Mavis Osborne had the infants. I had known Mavis Osborne when she was at the Wanganui Tech (we were both students at the same time). Also we were at the Wellington Training College together. My stay at Apiti was very short as there was a re-organization of positions and the two year clause was suspended. I applied for the headmastership of Queen's Park School in Wanganui and was appointed to take over that school from February, 1948.

Queen's Park, because of my earlier associations with it, held a special place in my affections, and I had six very happy years there as head, in spite of the fact that I had a class as well as having to run the school. It was a demanding task, but I had a very able and loyal staff. Several of them I had known for years - Edith Bell the Infant Mistress, Phyllis Ward who had been a Probationer at the Avenue School with me, C.C. Grant the first assistant, rather difficult at times to work with, Colin Sedon who had been a pupil of mine at Wanganui Intermediate. The probationary assistants from year to year were often old pupils, and so I was very happy with them. Even the school committee had a number of former associates on it. Some of the most close working groups I ever taught came through my Standard 4 there. Our relations with other people was very good too. We used the Public Library and Museum quite extensively as they were so close, and whenever an opportunity came I took kiddies to see the Art Gallery which was just across the fence from the school. The neighbouring schools (Convent) were very friendly.

When it came to parting after six years it was like deserting the family. The school gave us a great farewell, speakers including J.B. Cotterill, M.P., Mr Price of the Education Board as well as members of the committee and headmasters' association. Then the kiddies gave us their farewell and we had gifts, a desk and a standard lamp. I was always sorry that I had to leave the Wanganui district to complete my teaching service. I had had every consideration from the board's officers, from inspectors and all in control of the schools. But the only school available to give me promotion was in Taranaki, at West End in New Plymouth.

While in Wanganui, particularly while at the Intermediate School, I was privileged to take part in several refresher courses, at Taihape, Palmerston North and Ohakune, where I was able to give a few ideas on art which in those days was beginning to free up from the old formal style.

West End School, New Plymouth was the first appointment where I had no class responsibility. For a while I was "lost" without the direct contact with the children, but I took every opportunity I could to visit the classes at their work without interrupting them. The work was made easier too as I now had a clerical assistant to do the office routine. The school almost ran itself, although there were times when I had to set out quite firmly the standards I expected, especially with some of the younger teachers; and occasionally I had to smooth down the ruffled feelings of some of the older ones who felt privileged because of their long association with the school.

There seemed to be more changes to staff than in Wanganui, but that was probably on account of its being a bigger school. But there was a solid core of very faithful workers who remained with me the four years I was there. And they would have continued if the school had not been disintegrated with the establishment of the Devon Intermediate alongside, which took our top classes and many of the teachers. The school dropped in grade and I was transferred to Fitzroy. lvan Pepperell, first assistant, went as head at Moturoa, Miss Lil Burton went as Senior Woman to Devon, and other teachers to schools around.

Fitzroy I found the least congenial of all my appointments. The staff and committee were very good and loyal, but the district generally resented any change from methods that had operated over the last forty years. The fact that the district was divided in itself reflected in the happenings at school. There was constant friction between committee and parents' organization, each guarding jealously its privileges and finances. In my contacts with parents I was usually well received, but one or two were very hostile toward the school, and sometimes I had to act almost as personal body-guard to some of the teachers. In some ways I was pleased to break the tension by leaving.

Leaving Fitzroy meant severing my connection with the teaching profession as I retired from there on superannuation after just over forty two years of service. I should like to have continued for another two or three years, but I had already been two years over-scale and there was not another school in Taranaki to which I could be transferred. So that, to continue at the grade 5 salary I was getting it might have been necessary to travel to any part of New Zealand, and for the doubtful benefit of an extra year or two I felt it was not worthwhile. I had always intended to teach until Robert had completed his secondary schooling, but it didn't work out that way.

Even before I had retired, Jack Webster had asked me to take part-time teaching at the New Plymouth Boys' High School, and, as soon as I was available for this I took up that work. It was in many ways hard and unrewarding, so many of the boys, who were in the lower streams, resenting the fact that they were being taught by someone from a primary school, which they considered they had finished with. Some were delightfully co-operative, but one or two in each group made a worrying job out of what could have been pleasurable, both to them and to me.

I found that the association with the teachers of the high school gave me a different idea of the secondary service. They were friendly and helpful and not in any way exclusive as I had anticipated. Many of them had, themselves, been in the primary ranks, and many I had known before I went there. I retain a very warm feeling for such people as "Mac" McKeon, Jim lnsul, Les Slyfield, Bob Halliburton, "Pov" Veale, Alanic Wilson, Pat Huggett, John Hatherley, Owen Oats, Tom Watt, Dicky Baunton and Tom Atkins as well as numbers of others.

My association with the school came to an abrupt termination with a most unexpected fall from my usual high standard of health. I was suddenly subjected to an attack of angina, and although I went back in the following year for a couple of periods each week to give flute lessons, my active teaching was finished, particularly when a second attack laid me up at the end of 1964.

Early Recollections

Written by A. C. Barnes, about 1965 I[2] think.

By Way of Introduction

The young people I meet round about have all grown up in the age of television and jet travel, and I sometimes wonder how they regard the way of life as we knew it in the early years of this century. We who have grown up from the days of the horse have seen modern amenities develop gradually, but for the younger folk to see us as we used to be, and see the conditions under which we lived, would be to transport them almost to a world of make-believe. So I am going to put down some of the things I remember of the world in which I grew up. And because this is a personal story, I am afraid I must use the personal pronoun a good deal, and I must also use the names of my family and friends, not to hold them up to praise or blame, but like the dates in a history book - as pegs to hang things on. Most of the facts I shall be recording are remembered from my first years on a bush farm nearly forty miles from Wanganui, in the Mangamahu district, but some of them come from later experiences in the Waverley hinterland. In both places the conditions were very similar, and, although in the more settled areas improvements in the living standards were beginning to become general, the back-block people were still pioneers in every sense of the term. When we left Mangamahu in 1907, there was, I think, one motor car in the Wanganui district; there was not a mile of sealed road; many of the streams were unbridged; a few miles of distance meant an impossible journey. More thought and planning went into the arranging of a holiday ten miles away, than is necessary today for a trip to Australia. Perhaps that is why I remember only one holiday away from the farm until the time came for us to leave it. But there was much in the day-to-day activities to make life full and interesting.

The Home We Lived In

The house we lived in was not the first house that had been built on the farm. The first house was a slab whare with only a dirt floor. How long the family had lived in it I am not sure. I remember it as one of the sheds on the farm. But the first consideration was to get land cleared so that stock could be carried. Then thought could be given to the building of a more comfortable home. For this purpose, suitable trees were selected for felling, and saw-pits constructed for sawing up the logs into timber. This was a strenuous job. A flat-bottomed pit was dug on the hillside and a frame of heavy beams erected over it to take the weight of the logs. The long beams at the sides, and the end cross beams were firmly fixed in place, but a third crossbeam was not fastened, but free to move backwards or forwards according to the position of the saw-cut. When the log was levered on to the pit frame, and lined up, it was fastened by iron dogs to keep it in place. These dogs were iron bars about two feet in length, and having sharp points at each end. When in place, the log was first cut down the centre with a huge breaking-down saw, after which the two halves were sawn into the smaller sizes with a lighter saw. So that the saw-cuts would be in straight lines, a mark was made along the log where the cut was to go. For this purpose, a cord covered with lamp-black was stretched along the log and when tight it was flicked, leaving a straight, clear line which the top man was able to follow. The sawyers worked in pairs, the man on top of the log moving backwards ahead of the saw, while the pitman down below moved forward behind the saw. The handle at the bottom was detachable to enable the saw to be withdrawn from the cut. As the logs were cut up the piles of timber alongside the pit grew, being sorted according to size as they came off the pit. Thus almost at a glance the men could tell how much of each type of timber they had produced.

When the timber was assembled on the site, the building of the house could begin. Foundation blocks were set in the ground, and the building process followed on almost the same lines as the builders use today. In the remote areas the chimneys were a problem. In our case the bricks were home-made. A pit was dug in a clay bank, and the clay, when mixed thoroughly with water, was set into home-

made moulds and dried. Then they were fired in a crude fire and were ready to use. Our house was built on a simple plan, a square front part covered by a hip roof, and a lean-to across the back. The general set-out of the rooms put the parents' bedroom and the older girls' room in the front, separated by a short passage, and behind that the living room with two small bedrooms leading off from it. A small part of the lean-to was another bedroom, but most of it was the kitchen. The laundry was a separate shed behind the house and the toilet was a small outbuilding some distance away. The whole homestead was at the top of a bank of the river that at this place formed the boundary of the farm.

Surrounding the house was a fine garden and orchard where grew some of the finest fruit trees I have ever known - many varieties of apple, plum, pear, mulberry, and small fruit. The orchard was Grandfather's pride and joy. He had been trained in that work in Kent before coming to New Zealand in 1841, and his gooseberries trained up like standard roses are the only ones I have seen grown that way. But let anybody touch one of Grandfather's trees without his permission and the wrath of heaven would descend!

We were fortunate that my father was a builder, as he was able to construct all the buildings needed on the place. In fact, much of the running of the place was left to the older members of the family while he was away on building contracts to earn some ready money to finance his growing responsibilities. As the older boys grew up, too, they were often needed by the neighbours to help with the farm work, and so were able to earn some pocket-money.

In the house all the work was,done by Mother and the older girls. When I was old enough to notice such things, our cooking was done on a range with a woodburning attachment projecting in the front. But in the earlier years most things were cooked in camp-ovens over an open fire. This was very hot work for the cook. A metal bar with chains suspended from it allowed the camp-oven to be placed high or low above the fire, according to the degree of heat needed in the cooking. Bread needed embers below and on the top, and was usually done at one side of the fire, where a uniform heat could be maintained. Well-baked camp-oven bread has a taste that nothing can equal!

Bread-making days were Tuesday and Friday. The yeast was saved in a preserving jar from one baking to another, and the night before baking day, a lisponge" was made of potato-water, sugar, etc. and left overnight to set, so that in the morning it had risen to fill the special saucepan that was used for no other purpose. Then on baking day the flour, mixed with a little salt was set out in a huge mixing basin with a hollow in the centre of the mixture, and the sponge mixture poured in and gently mixed together. Later came the kneading, with time allowed for the yeast to cause the dough to rise, and after a couple of risings it was divided up into loaves, that were cooked in a moderately hot oven.

Another regular household task was the making of butter. As the milk came morning and evening from the milkers, it was taken to the dairy where the surplus not wanted for use as liquid milk was poured into wide, round enamelled vats and allowed to set until next morning, by which time the cream had risen to the top, and this was skimmed off into a bowl. In two or three days there was enough in the bowl for churning. After the churn had been scalded, the cream was put in it and the beaters turned with the handle. That seems a simple process. In fact, it was one o the most unpredictable. Sometimes the little lumps of butter began to form in about ten minutes; and sometimes after half an hour the cream was still liquid! Some people had queer notions about churning the butter. I remember once staying at my Uncle Dick's place, and watching him do the churning, a job he always did himself. Seated on a bench beside the dairy he turned the handle for ages. But he wouldn't let me take a turn because I might turn it the opposite way, and according to his belief, would turn the butter back to cream!

When the butter was finally made, washed and worked, it was put up into pounds. Usually these were the well-known rectangular shape, but sometimes an old butter-mould that had been Grandfather Old's was used, and we would see a model of a long-tailed sheep imprinted on our dish of butter.

Meat was always farm-killed mutton except for the rare occasions when somebody in the neighbourhood killed a bullock, in which event those on nearby farms shared the meat. Sometimes the others bought the meat, but usually killing was done in rotation and all shared. Later on when my brothers had the farm at Moeawatea, there were times when a group of neighbours would organise a hunt for wild cattle in the bush. This could be very dangerous, as some of the cattle were very unpredictable, and on more than one occasion one of the hunters would be treed until one of the others came near enough to shoot the animal. Both at Mangamahu and at Moeawatea there were wild pigs which provided both meat and sport.

Pig hunting could be really exciting. My participation was very limited, but I have listened with great interest to the tales John and Albert have told. If the dogs got on to pigs in the bush, that was usually the signal to drop everything and give chase. Sometimes they had rifles with them, and sometimes they did not, and then anything they had been using was the hunting weapon. Once Albert had been cutting grass-seed, and his only hunting tool was the sickle. With this he killed a young animal by throwing the sickle and inflicting a mortal wound. His most audacious kill was when he knocked down a pig with a large lump of rock, and while it was stunned his mate jumped in and grabbed it, turning it over so that they could kill it with a knife.

I should like to say that both the older brothers were good shots, particularly Albert, who was also very good at judging distances. If he said a pig was four hundred yards away, that would be within a few yards either way. His favourite target was a line of pigs moving up-hill away from him. His usual weapon was an old army rifle, .303.

But hunting was only a pastime, usually on Sunday, while the rest of the week was spent in such tasks as bush-felling and land clearing, fencing, (when fencing materials were available) and the multiplicity of jobs that have to be done on a farm.

One of the worst features of a back-block farm is its isolation, although this engenders a self-reliance often not found in people who have more ready access to the amenities of more comfortable living. We had to find our own playthings. I remember making sheep yards with chips from the wood-heap, and using the hard seeds from some of the trees for the sheep. We also at an early age learned to use some of Dad's tools - the really sharp ones were usually well out of our reach. Sometimes, however, they weren't, and I have a few scars still where chisels or sharp axes cut something they were not intended for. When one of us was hurt, Mother was the doctor. She had quite a flair for first aid, and if any of the neighbours was sick, or hurt, somebody would ride over to see if Mother could go to the home. She had a calm approach which immediately put the patient's mind at ease, and went a long way towards the beginning of recovery. In case of an accident she dressed the wound with gentle hands, if necessary applying one of the simple remedies that a doctor friend had recommended that she keep on hand, or resorting to old family "cures", or sometimes turning to the knowledge of the curative properties of native plants learned from the Maoris.